They Saw A Frail 92-Year-Old Man With A Faded Tattoo And Thought I Was An Easy Target To Mock, But When They Broke My Cane And Laughed At The ‘Chosen Few’ Ink On My Chest, They Had No Idea They Were Standing On A Landmine That Was About To Explode—And They Certainly Didn’t Expect 500 Marines To Answer The Silent Call Of A Brother In Arms.

PART 1: The Echoes of Winter

My name is Arthur Hayes, and at 92 years old, the world usually looks through me. I am part of the furniture of this town—a wrinkled fixture on a park bench, weathering away like the paint on these old picnic tables.

It was a Thursday afternoon in Ohio. The sun was high and hot, a blistering heat that most people my age complain about. But not me. I unbuttoned the top of my old plaid shirt, letting the warmth hit my chest. I crave the heat. I have craved it every single day for the last seventy-two years. When you have felt the cold that I have felt—a cold that freezes the fluid in your eyes and snaps steel like glass—you never complain about the sun again.

On my chest, exposed to the light, sat the ink. It’s faded now, blue-black and blurry against my papery, liver-spotted skin. An eagle, wings spread, talons clutching a broken chain. Below it, the words are barely legible unless you know what you’re looking for: The Chosen Few.

I was lost in a memory, watching a squirrel dart across the grass, when the peace was shattered.

It started as a low rumble, then a roar that vibrated in the hollows of my bones. A pack of bikers. They pulled up to the curb, engines screaming, chrome glinting aggressively. There were six of them. They killed the engines, and the silence that followed felt heavy, charged with a static electricity I hadn’t felt since the perimeter wire at the Reservoir.

They swaggered over. They were loud, taking up space, projecting that desperate need to be feared. Their leader was a mountain of a man. He wore a cut-off leather vest, and his arms were a gallery of vibrant, modern tattoos—skulls, flames, demons. He looked like he was carved out of granite and bad decisions. His name, I would learn later, was Spike.

He stopped right in front of my table. His shadow fell over me, blocking out my sun.

“Hey, old timer,” he grunted. His voice sounded like gravel in a cement mixer.

I didn’t answer immediately. I just watched his hands. You always watch the hands.

He pointed a thick, grease-stained finger at my chest. “Is that thing supposed to be real?” He laughed, looking back at his posse. “Looks like you got it done in a prison basement with a rusty nail and some shoe polish. What is that? A chicken?”

One of his lackeys, a wiry man with a bandana, snickered. “What’s the matter, Grandpa? Cat got your tongue? We’re talkin’ about that ink. The Chosen Few. What’s that? Your old bingo club? Or is it the few who remembered to take their pills today?”

The laughter that followed was harsh, barking, devoid of any real joy. It was the laughter of bullies who have never been punched in the mouth.

I slowly lifted my head. My neck is stiff these days, and it takes a moment. I looked into Spike’s eyes. They were brown, dull, and arrogant. He was waiting for me to look away. He was waiting for the fear. He wanted me to tremble, to button my shirt, to apologize for existing in his space.

But I didn’t tremble.

“It’s been a long time,” I said. My voice is quieter now, raspier than it used to be, but it’s steady.

Spike scoffed, crossing his massive arms. “Yeah, a long time since you had a coherent thought, maybe.” He leaned in close. I could smell him—stale beer, cigarettes, and unwashed denim. “I bet you paid some guy five bucks for that scratch after the war, tryin’ to look tough. But you don’t look tough, old man. You look pathetic.”

My hand rested on my hickory cane. It was a simple thing, worn smooth by decades of use. I didn’t grip it tight. I just held it.

“Leave him alone,” a voice cut through the humidity.

I shifted my eyes. It was Sarah. She’s a waitress at the food truck parked near the playground. A sweet girl, maybe twenty-two. She reminds me of my granddaughter. She was wiping her hands on her apron, her face pale but her jaw set.

Spike turned to her, flashing a predator’s smile. “Mind your own business, sweetheart. The adults are talking. Go flip a burger.”

He turned back to me, and then he did something that made the world stop. He reached out and poked my chest. His finger dug into the loose skin right beside the eagle.

“Doesn’t even feel real,” he sneered. “Just a smudge…”

That touch.

That single, disrespectful, dismissive touch.

It wasn’t the pain. It was the invasion. And in a heartbeat, the green park in Ohio dissolved. The heat vanished. The smell of summer grass was replaced by the stench of cordite, unwashed bodies, and frozen blood.

I wasn’t 92 anymore.

I was 20.

I was on a desolate, wind-scoured ridge overlooking the Chosin Reservoir. It was December 1950. The temperature was thirty degrees below zero. The wind didn’t blow; it shrieked. It cut through four layers of winter gear like a razor blade.

We were the First Marine Division. We were surrounded. Eight distinct Chinese divisions—120,000 men—against our 15,000. We were trapped in a frozen bowl of hell, outnumbered ten to one.

I could see it vividly. The gray-blue snow. The way the enemy attacked in waves, blowing bugles and whistles in the dark, a psychological terror that never ended. I remembered the sound of the frozen earth cracking under the mortar fire.

I remembered Dany. My best friend. A kid from Brooklyn with a laugh that could fill a mess hall. We were in a foxhole we had to carve out with explosives because the ground was too hard for shovels. Dany was talking about his girl back home, about the Italian food his ma made.

Then the shell hit.

There was no scream. Just a pink mist and the silence. The sudden, absolute silence where his laugh used to be.

“Look, I think we broke him,” the wiry biker chuckled, pulling me back to the present.

I blinked. The snow faded, but the cold remained inside my chest. I looked at Spike, but I saw the enemy. I saw the face of the man who tried to kill me on Hill 1282.

My hand slowly clenched into a fist. A single tear, hot and stinging, leaked from my eye and traced a path through the deep ravines of my cheek.

They thought I was crying from fear. They didn’t know I was crying for the boys who never got to grow old. I was crying for the sunshine they never felt. I was crying because this piece of trash standing in front of me, breathing free air, had no idea that his freedom was paid for with the frozen blood of better men.

Sarah saw the tear. Her grandfather had served in Vietnam. She told me once that she knew the “look.” The thousand-yard stare. She recognized the tattoo, too. She’d watched the documentaries.

I saw her pull out her phone. She didn’t dial 911. She knew the police would just come and take a report. This was different. This was a desecration. She dialed a number her grandpa gave her—a direct line to a local Marine Corps veterans’ outreach network.

I heard her whisper, her voice trembling, “There’s an old man… a veteran in the park. He has a Chosin Few tattoo. Some bikers… they’re harassing him. Please. He looks so alone.”

Spike was getting bored with my silence. He wanted a reaction, and he was going to take it.

“Alright, I’m done with this spook,” he growled. He reached down and snatched my cane.

“No,” I said, the first sign of resistance.

“Yes,” he mocked. “I’ll take a souvenir. Something to remember the ‘war hero’ by.”

He held the hickory stick up with both hands, placed it over his thigh, and flexed. With a sickening crack, the wood splintered. My cane, the thing that held me upright for twenty years, fell in two pieces to the grass.

“Oops,” Spike grinned. “Guess they don’t make ‘em like they used to. Just like you.”

I looked at the broken wood. I looked at my legs, trembling not from fear, but from the effort of standing without support. I felt a rage building in me, a volcanic heat that threatened to stop my heart.

But then, the ground began to shake.

PART 2: The Tide Turns

It wasn’t the erratic, jagged vibration of a motorcycle engine. This was different. It was a low, rhythmic thrumming. It was a heavy, synchronized bass note that you felt in your teeth.

Spike frowned, looking toward the park entrance. “What the hell is that? More of your nursing home buddies coming to nap?”

The sound grew louder. Deep. Powerful. Ominous.

Over the rise of the park road, the sun glinted off a windshield. Then another. Then another.

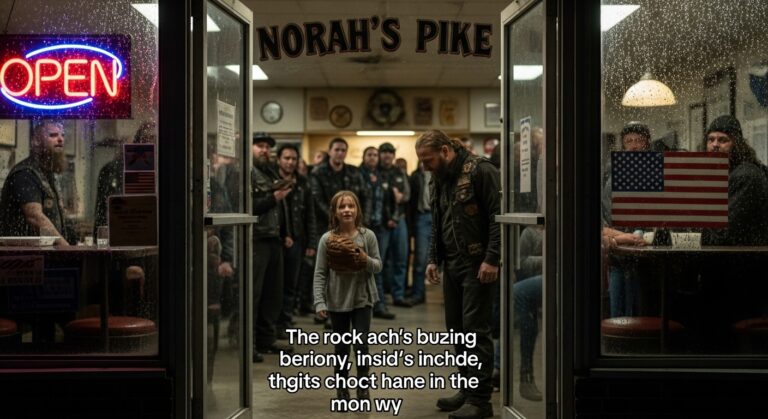

A Humvee, painted in woodland camo, crested the hill. Behind it, a black passenger bus. Then a convoy of pickup trucks, sedans, and motorcycles—not choppers, but disciplined touring bikes.

They didn’t speed. They moved with a terrifying, predatory slowness. They filled the parking lot. They parked on the grass. They blocked the exit.

The bikers went silent. Spike dropped his arms. The smirk slid off his face like grease.

Doors opened.

Boots hit the pavement.

One by one, they stepped out. First a dozen. Then fifty. Then a hundred.

They were young men with high-and-tight haircuts and jawlines you could cut glass with. They were old men in wheelchairs wearing VFW caps. They were women in business suits. They were men in construction vests. Some wore Dress Blues, pristine and sharp enough to slice the eye. Others wore combat fatigues. Most wore civilian clothes, but they all wore the same expression.

It is a look that says: We are here. And we are not moving.

The bikers stood frozen, their mouths slack, as the number swelled. Two hundred. Three hundred. Nearly five hundred Marines formed a semi-circle around the picnic area.

The park fell into a profound silence. The birds stopped singing. The wind seemed to hold its breath. Five hundred pairs of eyes were fixed on one spot: the small picnic table where an old man sat with a broken cane.

From the front rank, a man stepped forward. He was tall, wearing the Dress Blue uniform of a Colonel. His medals caught the sunlight—a rack of ribbons that told a story of service in Iraq, Afghanistan, and places the news never heard of.

He walked past the bikers. He didn’t look at them. He walked through them as if they were smoke. To him, they didn’t exist.

He stopped three feet in front of me. He snapped his heels together. The sound was like a gunshot.

He drew himself up to his full height and executed a salute so slow, so sharp, and so full of reverence that it made my throat tight.

“Sergeant Major Hayes!” the Colonel’s voice rumbled across the lawn, loud enough for the back ranks to hear. “Reporting as ordered, sir!”

I used the table to push myself up. My legs screamed, but I forced them to lock. I stood. I couldn’t return the salute properly—my shoulder doesn’t work like it used to—but I gave him a nod. A Marine’s nod.

“Colonel Evans,” I said, recognizing him from the V.A. hospital visits. “You didn’t have to come all this way.”

“The hell we didn’t, Sergeant Major,” Evans said, dropping the salute but keeping the position of attention. “The Corps takes care of its own. We heard a legend was under fire.”

Slowly, terrified, Colonel Evans turned his head. He looked at Spike.

The temperature in the park seemed to drop twenty degrees. Evans’ eyes were cold, hard steel. He looked at the broken cane on the grass. Then he looked at Spike’s face.

“Do you have any idea who this is?” the Colonel asked. His voice was low, dangerous. A tiger purring before the pounce.

Spike shook his head. He was sweating now. “I… look, man, it was just a joke. We were just…”

“This man,” Colonel Evans’ voice rose, projecting to the silent army behind him, “is Sergeant Major Arthur Hayes. That ink on his chest? You laughed at it? That is not a decoration. It is a seal of history.”

Evans took a step toward Spike. Spike took a step back, bumping into his bike.

“He is one of the Chosin Few,” Evans continued, his voice booming. “November 1950. He survived the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. A two-week fight in sub-zero hell. Surrounded. Outnumbered ten to one. No air support. No supplies. Just guts and bayonets.”

Evans pointed a gloved hand at me. “As a 20-year-old buck sergeant, he held the line on Hill 1282. When his machine gunner was decapitated, Sergeant Hayes manned the gun. He fired until the barrel glowed red hot. He burned the skin off his palms. When the ammo ran out, he fought with his entrenching tool. He fought with rocks. He fought with his bare hands.”

The Colonel leaned into Spike’s face. “Of the forty men in his platoon, only five walked off that hill. He carried two of them on his back. For that, he was awarded the Navy Cross. He has spilled more blood for this country in one afternoon than you have in your entire miserable life.”

The silence that followed was deafening. Every Marine in that formation was staring at Spike. It was a wall of judgment.

“And you,” Evans whispered, the sound hissing like steam, “you broke his cane.”

Spike looked at me. For the first time, he actually saw me. He didn’t see a frail old man anymore. He saw the survivor. He saw the ghost of the boy on the frozen hill.

Shame is a powerful thing. It hit him hard. His face crumbled. The arrogance drained out of him, leaving just a scared, stupid man in a leather vest.

He dropped to his knees. He didn’t mean to, I think his legs just gave out. He reached out and picked up the two pieces of the hickory cane.

“I… I didn’t know,” he stammered, his voice breaking. “I’m sorry. God, I’m sorry.”

I looked at him. I could have hated him. God knows I’ve hated men for less. But hate takes energy, and I didn’t have much left.

“Son,” I said. The crowd went silent to hear me. “It’s not about knowing my resume. It’s about decency. You don’t need to know a man’s war record to treat him like a human being.”

I looked at his friends. They were studying their boots, ashamed to look up.

“You think strength is loud,” I told them. “You think it’s engines and leather and intimidation. But real strength? Real strength is quiet. Real strength is doing your duty when nobody is watching. Real strength is getting up one more time when the world has beaten you down a thousand times.”

I reached out. Spike handed me the broken pieces of the cane. His hands were shaking.

“This one is done,” I said softly, looking at the splintered wood. “But it’s okay. It served its purpose. Just like we did.”

“I’ll buy you a new one,” Spike said, tears actually welling in his eyes. “The best one money can buy. Ebony. Silver. Anything.”

“Just go,” I said. “Go and live a life worth the sacrifice we made for it.”

Spike nodded. He stood up, signaled his crew. They didn’t rev their engines. They started them quietly, turned their bikes around, and rolled out of the park with their heads down. They passed through the parted sea of 500 Marines, shrinking under the weight of the gaze of the few, the proud.

When the bikes were gone, Colonel Evans turned back to me.

“Formation!” he barked.

Five hundred heels clicked together.

“Present, ARMS!”

Five hundred hands snapped to brows.

One by one, the formation broke into a single file line. From the youngest private, fresh out of boot camp, to the oldest veteran leaning on a walker. They approached me.

Sarah, the waitress, stood off to the side, crying openly, filming it all.

For the next hour, I didn’t sit down. I stood. I stood on my aching legs. I stood for Dany. I stood for the boys frozen in the ice of 1950.

Each Marine walked up, looked me in the eye, shook my hand, and said the same thing.

“Thank you for your service, Sergeant Major.” “Welcome home, sir.” “Semper Fi.”

I am Arthur Hayes. I am 92 years old. My tattoo is faded. My cane is broken. But as I stood there, feeling the grip of my brothers and sisters, I realized something.

I am not old. I am not frail.

I am a Marine. And we never stand alone.